The Failure — 997 Intake Manifold Valve Development

It began on a private member's day at Area 27 racetrack in Oliver, British Columbia. I was excited to drive one of my favorite tracks in the Pacific Northwest — and even more excited to be doing it in my favorite car: my Porsche 997 GT3 RS.

But shortly after my second session, something went wrong.

As I was rolling to a stop, the engine suddenly died. I assumed I had stalled. But when I turned the key, nothing. No crank. Just the lonely click of the starter. Confused, I thought something electrical had failed, and it would be an easy fix.

The car was towed to Kelowna Porsche, and after a quick inspection, they gave me the news:

“The engine won’t turn over by hand.”

My heart sank.

That’s the moment you realize you're not dealing with a minor glitch — you're staring down the barrel of a catastrophic engine failure. A failure on a Mezger engine isn’t cheap. The next call I made was to my trusted shop, Spec German in Gig Harbor, WA, and we arranged transport from Kelowna to Washington.

The Diagnosis: A Known but Underreported Failure

A few days later, I got a message from my mechanic:

“The intake flap fell into the engine.”

What?

I went straight to Rennlist and started researching. That’s when I discovered I wasn’t alone — there were other documented cases of 997 GT3 RS intake rod and flap failures, often catastrophic. But it still felt like something people weren’t talking about enough.

In the next blog post, we'll explore the failure mechanism and history of this issue. For now, let's examine the damage.

The Damage: What Happens When a Rod Enters a Mezger Engine

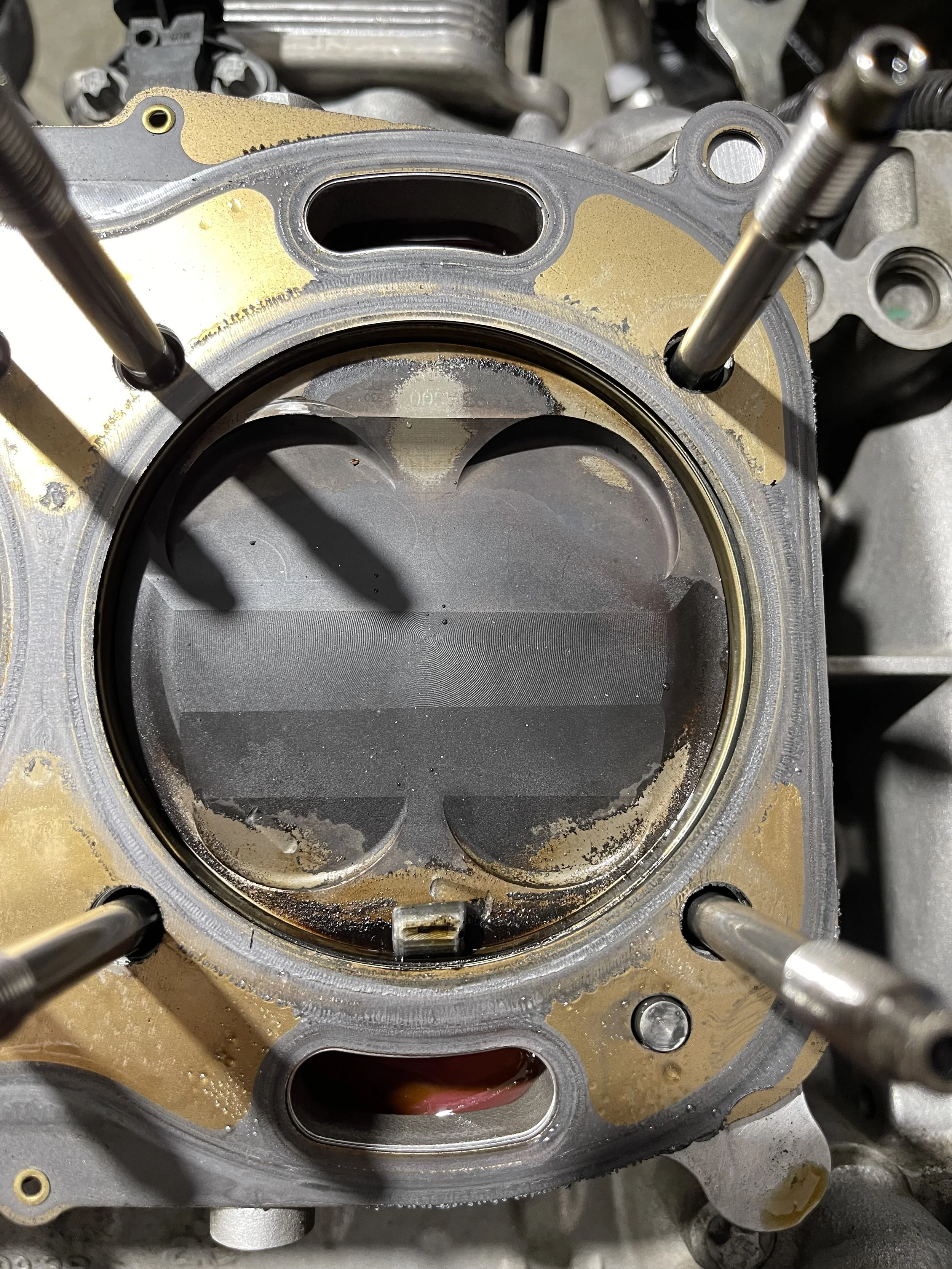

Below is a photo of what’s left of the intake valve rod — or rather, the part of it that made it into the combustion chamber.

You can clearly see:

The missing portion of the rod, sucked into the intake and partially ingested.

Damage to the piston crown, where the rod fragment made contact.

Breaks in two locations: one at the external rod connection (still inside the manifold), and the second — a clean break across the shaft — which perfectly aligns with the piece that resting itself on top of the piston.

Frankly, I’m lucky this happened while idling. If this had occurred at 8,400+ RPM, it wouldn’t have just scored the piston — it could have shattered the cylinder wall or punched a hole through the crankcase. The rod could’ve become a missile ejected from the engine block.

And in that scenario, the repair wouldn’t be a rebuild.

It’d be a complete engine replacement — a mid to high five-figure nightmare.

The Takeaway: Small Parts, Big Consequences

This kind of failure isn’t supposed to happen in a car like this. But it does.

And when it does, it can turn your day into a Mezger engine disaster.

In the next post, we’ll dive into:

Why do these components exist within the intake manifold

The history of this failure